An honor presented by Metro Service Group Celebrating Accomplishments! An honor presented by Metro Service Group Celebrating Accomplishments!

By: Bill Rouselle

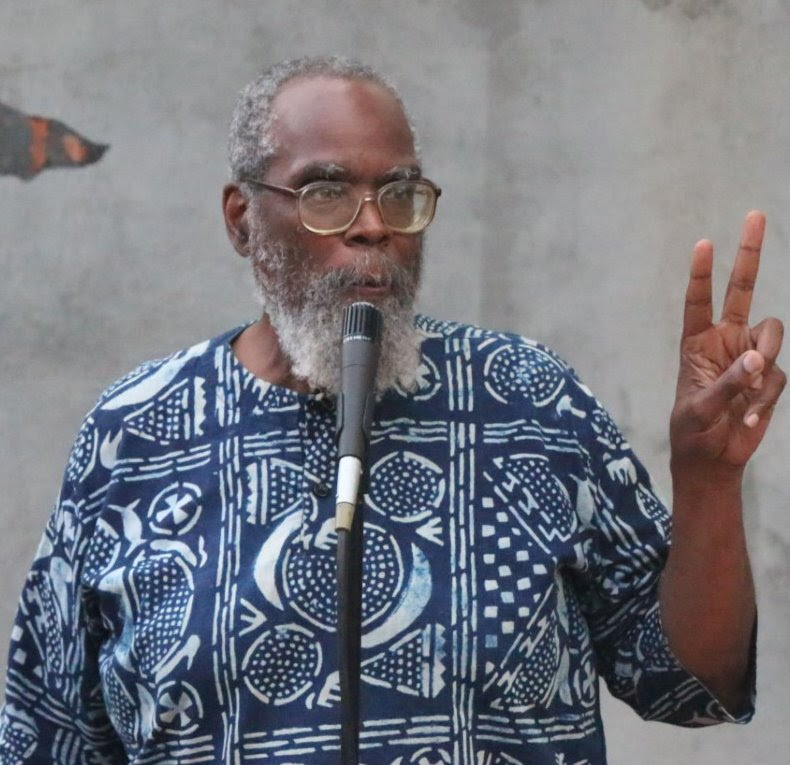

When Vincent Sylvain called to ask me to develop a Metro Tribute piece for my friend and former business partner, Kalamu ya Salaam, the words integrity – commitment – family – a fierce love of African people come to mind!

Kalamu ya Salaam is a son of the Lower Nine. The oldest son of Vallery Ferdinand, Jr., and. Inola Copelin Ferdinand, Kalamu and his two brothers Kenneth and Keith Ferdinand are three of the Lower Ninth Ward’s most well-known and respected “sons”.

Born, Vallery Ferdinand, III, Kalamu ya Salaam (which means Pen of Peace in Kiswahili) took his African name in his early adulthood. Before he finished high school, Kalamu was marching with the NAACP Youth Council protesting segregation, he finished high school in 1964 and served in the U. S. Army in Korea. Kalamu returned to New Orleans in the late 60’s imbued with a sense of his African self and totally committed to community organizing and institution building of a new African-American reality.

Kalamu was one of the lead organizers of the student takeover of SUNO in the late 60’s when the State of Louisiana began efforts to merge SUNO and UNO. The students took over the campus, took down the American flag and staged a walkout in protest of the merger efforts. They mobilized an on-going protest that resulted in the state backing off of the merger efforts.

In the 1970’s Kalamu and his then wife Tayari Kwa Salaam founded Ahidiana an Afro-Centric school for their children and many other young people in the Lower Ninth Ward community. The school taught from an African centered view of the world and challenged their students to be critical thinkers and active in their community. It is noteworthy that each of Kalamu’s and Tayari’s five children and all the young people who experienced the early Ahidiana education have grown into productive and committed adults.

He honed his writing skills as a member of Free Southern Theater’s Black Arts South writing group. And, perhaps Kalamu’s greatest contribution to our city and the world is hundreds of people he has touched with his poetry, mentored and developed into critical thinking people who will have lasting impact on their generation.

But, I’m getting ahead of Kalamu’s life of active community organizing and institution building. In the late 60’s he helped found and became editor of the Black Collegian Magazine, the only nationally distributed Black publication to be developed in New Orleans in contemporary times since historic endeavors by free people of color. Black Collegian was the brain child of Preston Edwards who saw the need to link Black college students to job opportunities that began to open for African-Americans as affirmative action laws were being implemented. The Black Collegian managed to remain a profitable venture through the 1970’s and in the late 1980’s, Black Collegian also developed an on-line platform during the heyday of the dot.com revolution.

During his tenure, as Black Collegian – Editor, Kalamu continued his community activism. He was one of a group of young activists who kept Black people’s issues at the forefront throughout the 1970’s and into the 80’s.

He led major organizing efforts around police brutality issues. The most memorable demonstration was the takeover of City Hall in protest to the police killings in Algiers in 1970.

A champion of the indigenous culture of the African centered New Orleans tradition, Kalamu fought for the inclusion of African-Americans into the Jazz Fest. During the mid-80’s Kalamu served as Executive Director of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival Foundation and I served a two-year term as President.

Kalamu and I put up $750 each to start a public relations company in 1984. Bright Moments is now in its 33rd year and is recognized as one of the leading African-American PR companies in the New Orleans area. Kalamu was the creative genius who established the Bright Moments brand and provided strategic and sound businesses practices that are the foundation of the company’s assets today.

By 1995, Kalamu had tired of the day to day hassles and compromises that running a Black PR company poses. He decided to dedicate his full-time energy to his writing and to mentoring young writers and artist in New Orleans. His prolific writings are available at his website “Neo-Griot” [www.kalamu.com/neogriot] and his mentoring evolved from a weekly writing forum NOMMO Literary Society to a creative writing course now offered at several New Orleans Public Schools – Students at the Center.

He is known internationally for his piercing intellect and sharp precise word crafting. He is a GIANT in the literary world of New Orleans and is held in high regard by those who know him best. I could not tell his whole story so I reached out to his family, friends and associates. Below are some of their thoughts about this man of PRINCIPLE – Kalamu ya Salaam.

His Brothers: Keith Copelin Ferdinand

In typical New Orleans fashion, with two older siblings, I was called the “baby.” As the youngest of the three Ferdinand boys, I had limited identity as a little brother until high school when I participated in a prep school quiz bowl on TV and I did well enough to stand out for myself and, for my family and friends, against white students at white schools.

The most important thing as Lil’ Val ‘s-our father was Big Val-lil’ brother was that he was well known by the New Orleans police from his being active in civil rights sit-ins and marches. Members of the Junior Chapter of the NAACP and other picketers would come to our house after protests and meetings for a hot, home-cooked meal and a place to safely relax.

Val taught me early, if I was going to borrow his car that I was definitely going to get stopped by the police. He made sure to show me and tell me everything I needed to know. Here’s the car registration. Make sure you have your driver’s license. Be sure to stop at every stop sign. Don’t give your enemies ammunition to use against you. Getting stopped by the police is not a time to fight a battle. When I borrowed his car, I would get stopped, yet I followed his directions and never had any problems. I kind of think the police were let down that I didn’t give them any objections, or they were just disappointed that they didn’t catch who they were looking for, my big brother.

One more anecdote…Our father was a military man, so was Val. I wasn’t, yet I gleaned some key lessons from them. You do what you supposed to do. Stand up for yourself. Then to hell with ’em. You don’t have to bend to please. Just always do what’s right.

Kenneth D. Ferdinand

My big brother, Kalamu ya Salaam wrote my life as a social activist and professional. Kalamu and I are less than two years apart in age and even closer in social and political development. I registered neighborhood residents for years in the Lower 9th Ward during my summers in high school. I listened to Coltrane and Miles for the first time in my life because of Kalamu. He loved jazz–really loved jazz and Kalamu was the cause of it all.

Kalamu helped me discover myself and my relationship to my world. My brother, Kalamu ya Salaam, was a primary force for justice in life. He was a commitment to freedom for all Black People as I knew him. He taught me to love my people as I loved myself.

Vallery Ferdinand III, as he was born, was a son of Vallery Ferdinand, Jr.–my Dad, and Rev. Vallery Ferdinand, Sr.–my Grandfather. Kalamu, the activist, the writer, the man was my great hero, guide and teacher. I love my talented and politically committed big brother.

He is the Man, especially as he celebrates 70 years of challenging the white supremacist men masquerading as leaders of America.

His First Wife: Tayrai Kwa Salaam

On the occasion of Kalamu’s 70th birthday . . .

Passionate and sensitive, Kalamu has a way with words, a writer’s writer.

Kalamu is a change agent, an agent of change. Wherever/whenever Kalamu is involved, seeds of transformation are planted and the possibility of revolution will grow.

We, Kalamu and Tayari, are forever comrades sharing thoughts, tasks, and institution-building.

One of our most remarkable and wondrous accomplishments as comrades are our five children who are living examples of our raising (provide, protect, respect, inspire, educate, socialize) who are living in their own way happy, healthy, self-satisfied citizens of the world.

Each moment of every day learn/teach, teach/learn. Life is a wondrous thang. NAMASTE. (A Hindi word meaning: “I honor the place in you where the universe resides, the place of peace, of joy, of love, of truth; and when you are there, and I am there, we are one.”)

His Current Wife: Nia (Beaulah McCoy) Salaam

Kalamu ya Salaam – Nia Salaam

My husband. His attributes include love, joy. peace, longsuffering, kindness, gentleness, faithfulness, goodness and self-control, but the greatest one is love.

I first encountered Kalamu in the community reciting and performing poetry, doing plays, and being involved in music.

In the early 70’s he was administrator of Lower Nine Health Clinic and I was the x-ray tech at the clinic. Kalamu was not a micro-manager. You knew what you had to do and he would leave you to do it.To this day, I say that was the best job I ever had.

We got together in the early 90’s and lived together until 1997 when I was robbed at gunpoint coming home. Wow! Kalamu was at a writer’s workshop. I was so upset! The police came and made a report and Kalamu came home. I was so afraid, I couldn’t stop crying thinking about what could have been. Kalamu held me in his arms and consoled me and said there was something he wanted to ask me, but he had not planned on it being this soon. He asked me to marry him. I said “What! and ruin a beautiful relationship!” Whether or not it would ruin the relationship, I said yes and we were married February 24,1997.We recently celebrated our 20th wedding anniversary and I can truly say it has been a wonderful marriage. We have not had any major arguments in the 20 years. He usually says what I say goes. Our house is peaceful and comfortable. Kalamu is usually on his computer and I am doing crafts, reading or following Donald Trump.

Since my stroke in November 2014, I have been unable to drive. I didn’t realize how much running around I was doing until I was unable to do it. Kalamu takes me to my appointments, classes, meetings, church, grocery, anywhere I have to go with no complaints. I feel a little guilty sometimes having to ask him to take me places, but he never complains, he just says “no problem” I really appreciate him for that.

Kalamu cooks. He has dinner for us every night. I remember when we didn’t have a stove and ate out most days of the week. It’s better at home.

I only have one complaint. He puts the toilet tissue roll coming from the bottom instead of over the top. Other than that, he’s a keeper and I love him.

His Children: Tutashinda Salaam

The thing I admire the most in Baba is that he marches to the beat of his own drummer…and the greatest gift he ever gave me was the gift of independent thought. Mtume Salaam

Several years ago I went with Baba to one of his poetry readings at a university in San Bernardino, CA. His reading was trademark Kalamu: emotionally and intellectually challenging; funny and fierce; pro-Black Revolutionary in both spirit and content. After he finished his reading, he invited students from the audience to recite poems of their own. Just as Baba was wrapping up, a woman sitting in the back raised her hand and said she’d like to read, if Baba wouldn’t mind staying. Baba invited her up to the microphone. It’s important to note that, until then, every writer had been young and black. This woman was middle-aged, white and conservatively dressed to boot. I thought, “uh oh,” then watched and listened with great interest as the woman read an extended piece written in strict iambic pentameter. When she finally finished, she received lukewarm applause, then the room went quiet. “Excellent,” said Baba, standing up and walking towards the mic. “Now let’s talk about that second stanza.” As Baba and the woman stood side-by-side at the lectern, discussing her work in detail, the rest of the audience filtered out or milled around, socializing. Later that evening, I remember asking Baba how come he’d spent so much time with that particular woman, especially when her writing and performing style-reserved, academic, and very British-was so far removed from his own. He shrugged and answered, “She’s a poet.”

Tiaji Salaam-Blyther

When I received the email asking me to submit one lesson or story about my father, I thought, “One?!” One story would fail to capture his fullness.

My father is a complex man made of opposing dualities, at once aloof and engaging, dismissive and empowering, cold and witty. These seemingly opposite attributes somehow combine to form a sage. As a child, it frustrated me when I would go to my father with a problem, carefully recounting whatever turbulent emotion I was experiencing. Him, sitting quietly, not interrupting. Patiently waiting for me to purge. After completing my tale, there inevitably was a pause. A silence that probably lasted half a second, but felt much longer. Although I knew what the response would be, I always hoped for a different answer. That this time would be different. That this time he would tell me what to do. Nope. Each time. The answer was the same. “What are you going to be about that?” I was so Frustrated by that answer. It felt aloof and dismissive. When I went to college and saw the immature state of my peers, I at once knew. That the answer that seemed to be the only one my father was capable of providing was actually empowering.

The lessons never end. The other day I called my father to tell him how much I appreciated his sharing his love of music with us. As we discussed his extensive album collection, he told me that the collection was mostly gone. I was incredulous! “Gone?! Where?!” The sage answered, “Here and there.” The more worked up I got, the more tickled my father became. I started running through all of the genres of music that he had. He patiently listened and then said, “You can download all of those songs you know?” I began to lecture my father about the virtues of albums, the unique sounds they bring. He indulged me and patiently listened, just as in childhood. But I am not a child anymore and our relationship has changed. My father actually offers advice now. In his own way mind you.

After I had exhausted all arguments lauding not only the unique attributes of albums but also their value, the sage responded. The pause remained but the answer differed. “It’s just stuff.” All I could do was laugh. Here I was worked up over the loss of something that wasn’t even mine to begin with and the man who actually lost his “stuff” was unnerved.

My father is the deepest well of unearthed wisdom. Cool, dark and still on the surface. Plunge beneath the surface and you will find your own wisdom. When I received the email asking me to submit one lesson or story about my father, I thought, “One?!” One story would fail to capture his fullness.

Kiini Ibura Salaam

There’s really too much to say about a parent, let alone one who has had such an intensely interesting and engaged life as Kalamu. His travels! His interviews of musicians and writers! The art he collected! The relationships he made! His book collection! His record collection! His activism! His individuality! His questioning of it all!

All of it filtered down to us as children as we lived within the music, art, words, activism, and rigorous interrogation of his life. I’ll admit that we Salaam children felt shortchanged. Why did our parents have to be the ones living creatively rather than comfortably, raising us philosophically rather than traditionally, insisting on a lifestyle that made us stand out rather than blend in?

And Kalamu is an imposing figure. My friends were afraid. Strangers perhaps terrified by this big bearded man in glasses. Despite his gruff exterior and disinterest in niceties and small talk, Kalamu is, at heart, a nurturer. Beyond parenting, he nurtured me as a writer. Encouraging me to submit my first story for publication and becoming my editor as I embarked on my path as a writer. He nurtured me as a traveler, always sharing his contacts (there seemed to be one in every corner of the world) and being there for me when I needed to call home. And now that I’m older, if I call him with an issue, he always wants to know, “What do you need from me?”

He connects with the younger generation in ways that men of his generation often don’t. His mind is open to ever-expanding forms and expressions and he appreciates the humanity in wide and disparate types of people. Kalamu–to me–is a dual insistence. His existence asserts that 1) we all have the right to be whoever we damn well please and 2) our unique expressions aren’t extinguished by someone else’s–there’s room for us all to be our full selves.

As an adult, I now know that my unorthodox upbringing was a gift. Sure, my parents didn’t coddle us. But they weren’t interested in infantilizing us or carrying our burdens for us (no matter how much we wish they would). They were committed to raising individuals who would have the wherewithal to stand in the clamoring chaos of this world and by unmoved, undiminished, and unafraid. For my strength, my individuality, my intellect, my lack of fear, and my self-reliance, I say thank you, Kalamu. You didn’t make it easy on us, but in the end, you gave us exactly what we needed to survive and thrive.

Asante Salaam

You taught me to give folks their flowers while they’re here, while they’re around to enjoy them. To appreciate and honor people in life.

You taught me to be connected and build relationships with people…people that I like, or not; all different kinds of people; because we are all mutual humans on this earth.

You taught me things your father taught you…that the road is too long, and it’s too dark out here…give people a ride so that they’re not out here walking alone. And giving a ride ain’t nothing to it–no matter how far along or far out the way.

You taught me that people are more important than things…about collecting anecdotes from close loved ones–lessons learned, appreciated accomplishments, treasured memories. And photos, too.

You taught me about ideology and theory in practice….that ideas are great, but ideas ain’t much if you ain’t doing nothing with it. If you ain’t in action. If you ain’t making change. However you see fit.

You taught me to believe in black people. And liberation. And revolution. For ALL people. And blues. And New Orleans. And film. And travel, not tourism. And words, yet drum and music, music, music, before words. And…

Of course, considering the hundreds and tens of thousands of people who you know, who know you, or know of you; the numerous folks who have learned from you, who appreciate so many things you’ve done–big and small, life changing and lastingly impactful; this is but a taste of all who are already celebrating–or would be honored and glad to celebrate your seven decades on this planet, in this dimension, for this lifetime with us all.

Reviewing your life in the little survey way I’ve done these recent days leading up to this birthday of yours, hearing folks’ knowings of you, reminds me of the so many things I too love and appreciate about you. So, I “Amen” each of them.

People He Mentored:

Don Paul worked with Kalamu on several occasions. Don is s poet. He is married to Maryse Dejean’s husband. He works with her for the children in Haiti.

KALAMU

Kalam took it seriously, the whole deal. That whole deal about being a cultural worker. About serving the people. Educating the young. Providing platforms that weren’t there before in schools, Festivals, airwaves, … Networking like a Thoth on fire with the power of connectivity, around the nation and world, before and after e-mail. And always loving the music-the drums that sustained identity and sanity in Congo Square, the horns that followed, the chordal progressions beyond folklore and Opera, and the dancing advances that grew.

Kalam, known by single name. A cultural warrior, too-readymade in New Orleans-strong and colorful men and women across the Wards-the Plantation of segregation and privilege as intrinsic and vicious as ever one century after Jim Crow days. Always standing fast. Always about the struggle for justice. About that for decades, Kalam, as decades rolled up, down and sideways. An Eagle, if you take the Eagle as life-giving myth willing, able and inspired to teach works of Langston Hughes, Henry Dumas, Ornette Coleman, Jayne Cortez, and Kidd Jordan evenings after school. Fire, if you see that image, that fiery image, as calling forth both tinder and inviolably resistant hardwood.

Kalamu took the whole deal seriously, the chances glorious for himself and us all to grow, and he still does.

kelly Harris-de

Before I moved to New Orleans, I was familiar with Kalamu ya Salaam’s poetry. Thankfully, the Black writing elders of my hometown made sure to teach his work.

His impact beyond New Orleans is monumental. His documentation and participation in the Black Arts Movement is a gift and blueprint for Black artists. When I moved to New Orleans I knew I had to meet Kalamu ya Salaam. I was excited and nervous. I knew I would need to connect with him before even thinking about doing poetry in the city.

Kalamu ya Salaam was the first poet to come to my house when I moved to New Orleans. It was like a personal workshop and introduction to New Orleans. He laid the foundation for how I would enter the community.

I’m grateful that he embraced me. I wasn’t in the NOMMO workshop.

When he wrote the introduction for my poetry CD, I called him and told him I didn’t think I was worthy of what he wrote. His response? So what are you going to do about it?

If you are going to be a student of Kalamu, there are no short cuts. You must read, study, write, and if you’re lucky-you may earn some props.

I admire his work ethic as a writer. He’s helped so many people become writers. His commitment to print and digital literary engagement should be celebrated for its longevity and relevancy in an ever-changing world. He is a resource even when I don’t see him.

Perhaps, Naomi, my 4 year-old-daughter, shows us how to best appreciate him. One day she was trying to pronounce the cover of his book, “The Magic of JuJu,”-she couldn’t quite make out how to pronounce the word “JuJu.” She exhausted herself trying and simply held the book up and made it plain. Look mama, Baba Kalamu! He magic.

Freddi Williams Evans – Author of Congo Square

Kalamu was the first person to call me a writer. He was and continues to be the primary influence on my work and has profoundly impacted on my world-view. As a member of NOMMO, I appreciated the way he accepted people like me who were willing to work, and how he embraced and engaged such a diverse group of writers. On any Tuesday, there were young, aged, novice and professional writers all working on different styles and at different stages of the process. Kalamu handled it all. Yes, he was and is brilliant, but it took more than that. Among other qualities, he was straightforward and consistent in his straightforwardness. “Leave your feelings at the door,” is what every newcomer heard. But actually, we were too embarrassed to read raggedy writing. After all our operational definition for NOMMO was “No mo’ of that B.S!” A more standard definition refers to the power of the word to create and generate reality.

At this moment I long for NOMMO because I need to ‘workshop this piece.’ I can’t find words that adequately express my gratitude to Kalamu for providing a place for us to gather and the space for us to grow; for showing up week after week demonstrating his commitment to us even when we were not always committed to ourselves and our work; for modeling good writing; for mentoring me through the writing and publication of awarding-winning children’s books and Congo Square: African Roots in New Orleans, which received the 2012 Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities book of the year award; and for continually being an anchor for black writers and an activist for our community.

Happy 70th Birthday, Kalamu and many, many more!

Love and blessings always,

Karen Celestan

Kalamu’s guidance and leadership through the NOMMO Literary Society opened my mind and spirit to new paths of reading and writing. Membership in that group was such a profound learning experience, better than any more traditional literary program. Gathering around a long table on Tuesday nights with potluck dishes and sparkling cider was not to be missed, and you had better bring material that worth being shared or you would have a moment of pure clarity about your work. What a lesson about “leaving your ego at the door!”

I will forever cherish the memory being in the presence of Sonia Sanchez and sharing a late meal with a few NOMMO members at the Trolley Stop on St. Charles with Kalamu and Amiri Baraka, laughing and talking shit. My life was changed forever and I am grateful to Kalamu for setting me straight when I was off-kilter and acting crazy, then turning right around to open so many doors with love.

|